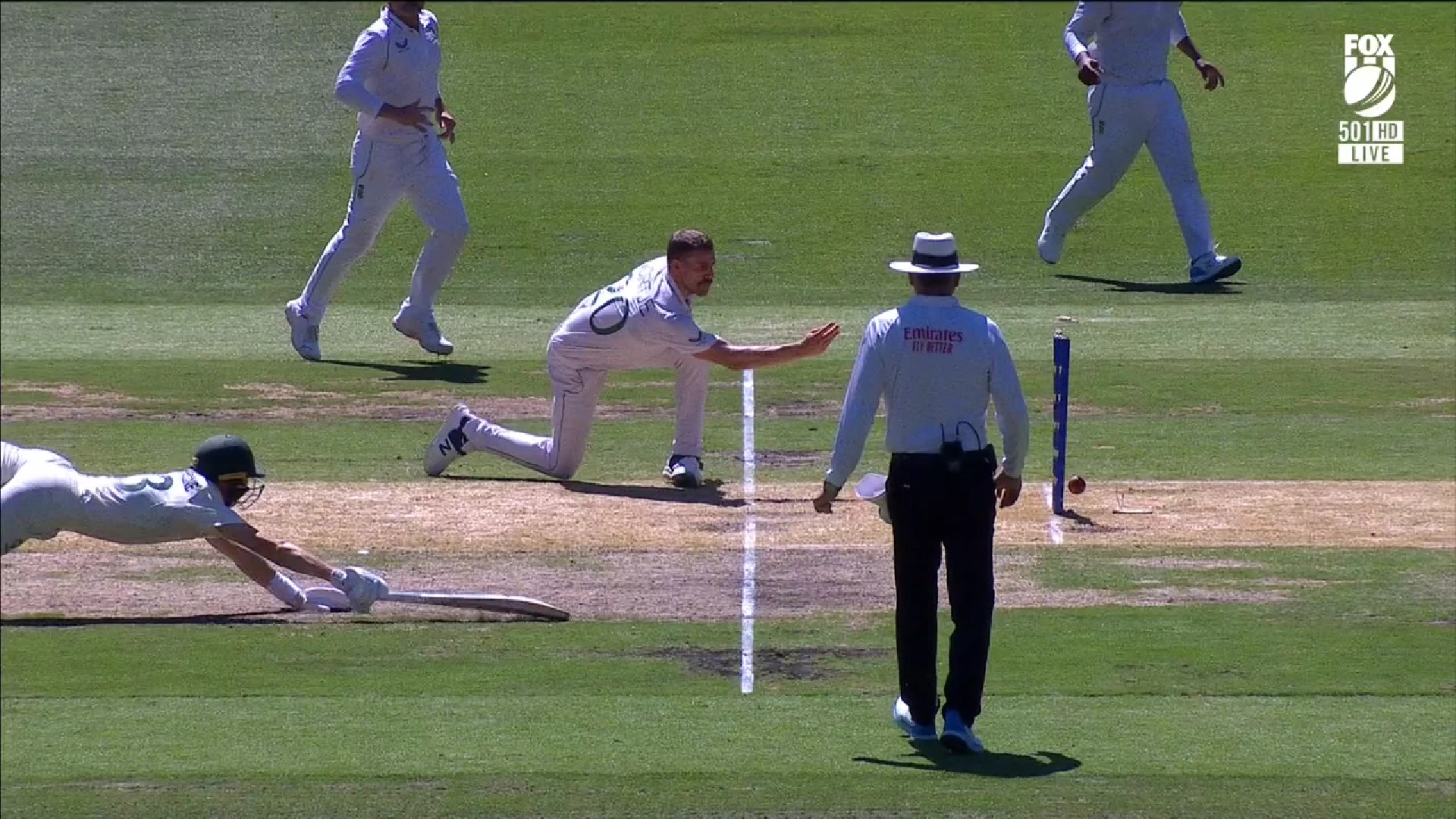

The instant Marnus Labuschagne’s desperate dive was beaten by Anrich Nortje’s underarm at the stumps by a matter of millimetres to give South Africa a crucial early breakthrough at the MCG, social media lit up in almost universal condemnation of David Warner’s role in the disaster.

As you can see, selfishness was a common theme in the criticism, with the Fox Cricket commentators praising Labuschagne for taking the bullet and sacrificing himself to keep the milestone man at the crease.

‘The most selfless thing we’ve seen in a long time,” enthused Kerry O’Keeffe.

“Marnus saw out of the corner of his eye how committed David was. David thought about turning back and going to the danger end, yet Marnus said ‘I’ll go’, despite the plight being completely gone for him.”

No doubt Warner deserves his fair share of the blame for the mix-up – he showed a lack of awareness in how far Labuschagne had gone past the crease to make his ground for the orginal single, setting into motion the chain of events that saw the number one Test batter in the world run out.

However, while it might be unpopular, it’s worth noting that Labuschagne was hardly completely blameless in the drama. And given he’s now been run out five times in his Test career – more than anyone else in the game since he debuted in October 2018 – it’s becoming clear that there are a number of flaws in his work between the wickets.

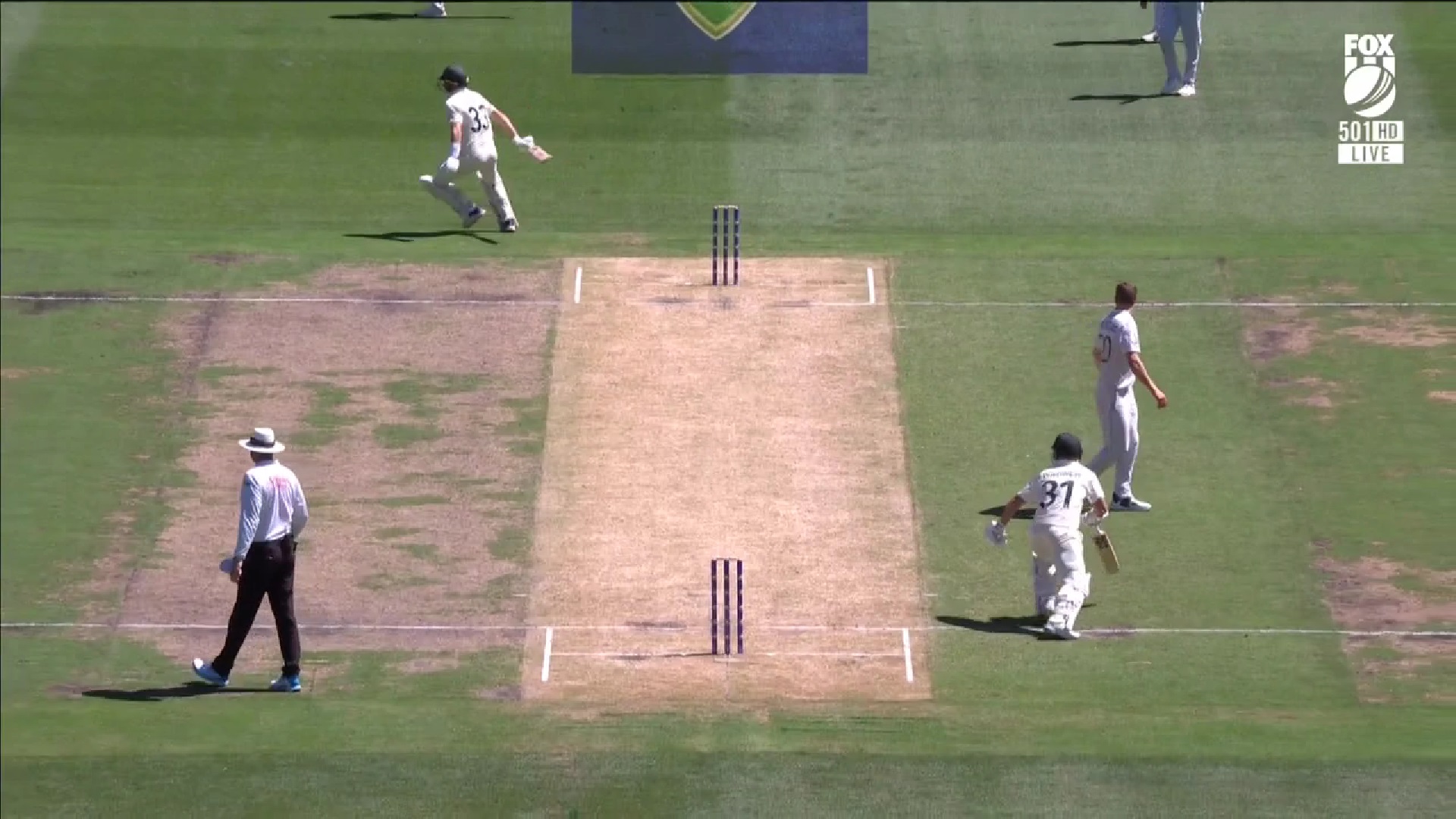

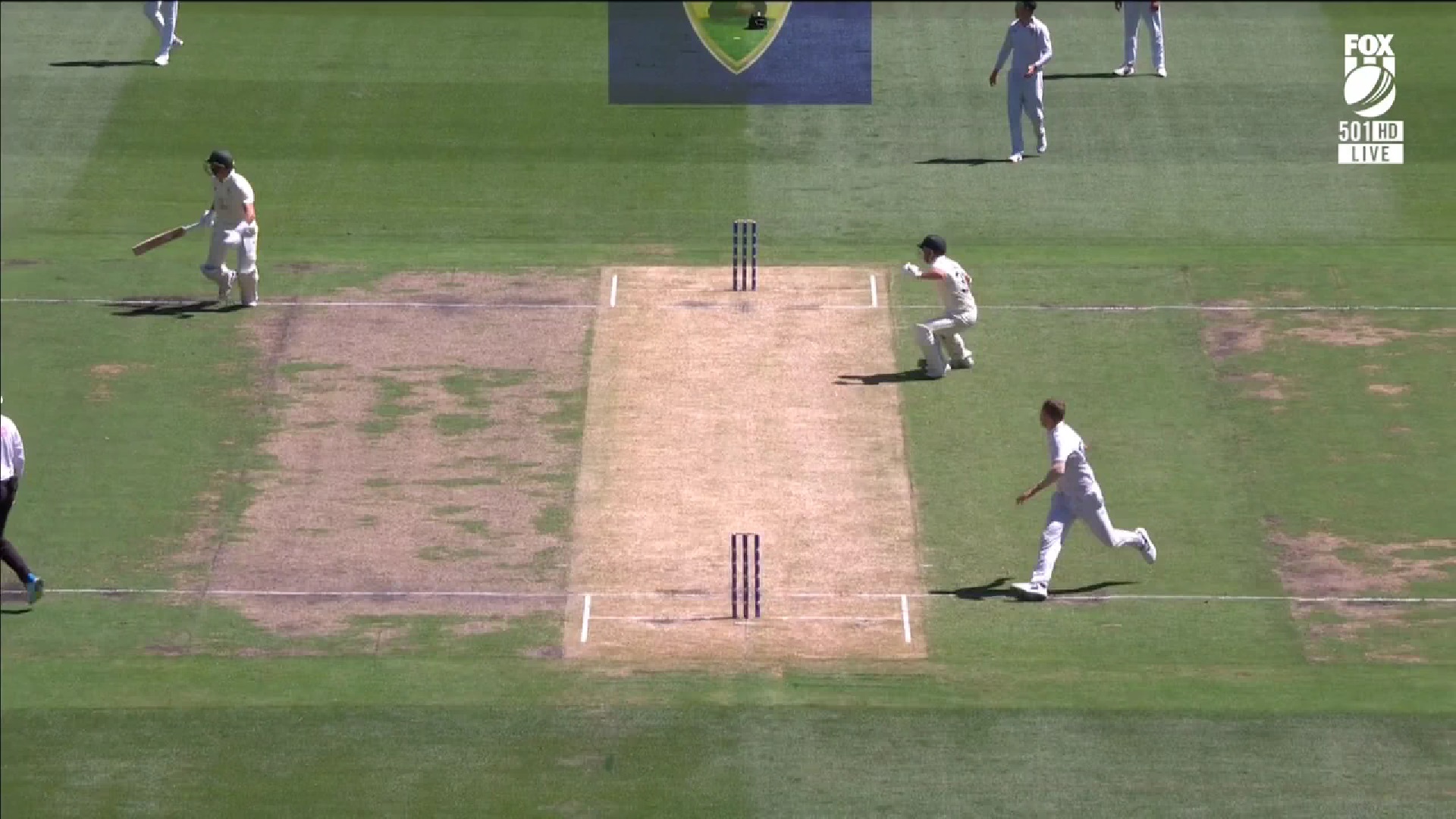

Let’s start with ground zero for the fiasco: Warner turning, noticing the ball had gone into the deep, and sensing the possibility for an overthrow run.

Image credit: Fox Cricket

Was there a run there? Well, we’ll get to that shortly, but this is where the ‘selfishness’ jibe is directed. How dare Warner take such a risk, and sell his teammate up the river, to try and steal an extra run.

However, it was Warner’s call, and he was going to what would have usually been the danger end for Keshav Maharaj’s throw coming in from backward point. Having not needed to put in a desperate sprint for his ground to carry him well past the crease, as Labuschagne had done, he backed himself to make the ground.

No doubt he thought as well that Marnus, despite having to run a few extra metres, could make his ground too, given the difficulty for Maharaj to get the ball quickly to Nortje at the non-striker’s end.

CLICK HERE for a seven-day free trial to watch international cricket on KAYO

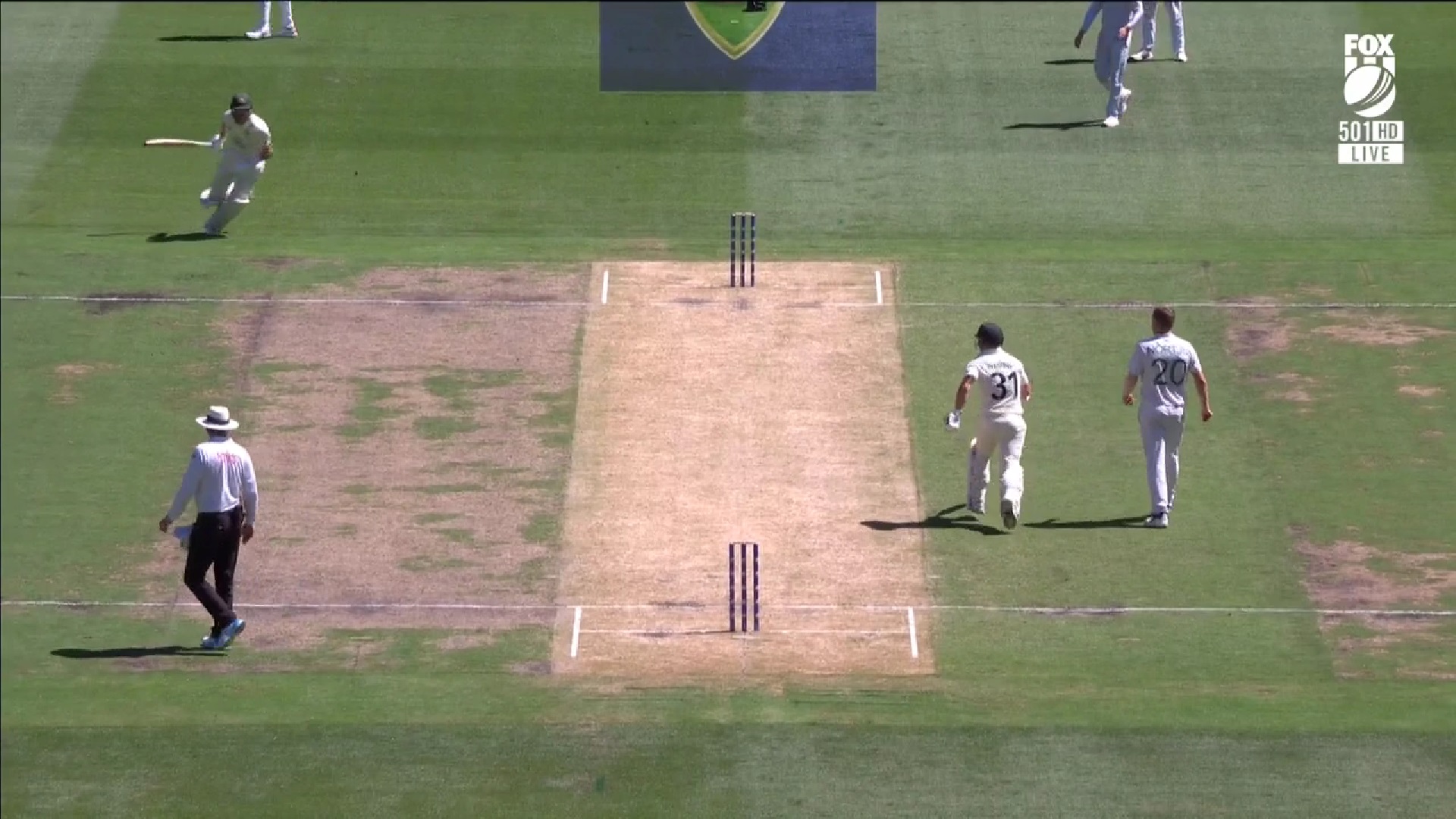

The next moment is where Labuschagne lands himself in trouble. A loud ‘No’ here puts the matter to bed; Warner hasn’t come down far enough that he can’t safely get back – the ball isn’t in Maharaj’s hands yet at any rate. If he assesses now that he won’t be able to make it, crisis can be averted.

Instead, he does the natural thing you do when your partner calls you for a run and it’s his call – he responds immediately, turns quickly, and starts running again.

Image credit: Fox Cricket

So far, Marnus has done everything right. But next is where things start to go wrong.

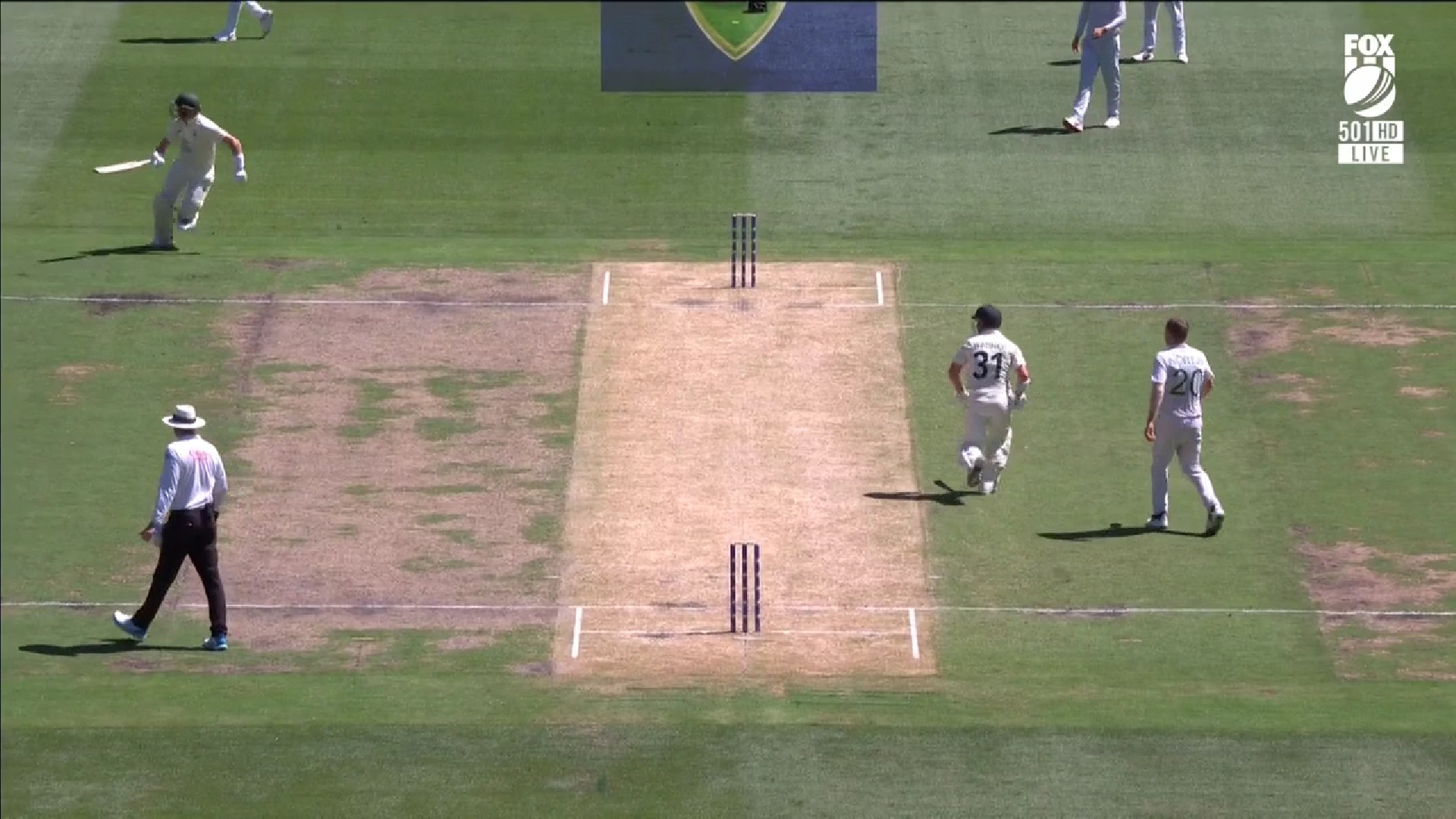

It would be harsh to blame Labuschagne for this, but as he’s running, he turns his head to watch the ball. It’s only now, as he sees Maharaj pick up the ball, that he realises trouble may be afoot.

Image credit: Fox Cricket

So many run outs at every level of cricket are caused by players ball-watching; it slows you down, and importantly, takes your eyes off your partner. The very best pairs at international level trust the other implicitly, and can put their heads down and sprint for the other end confident in the knowledge that they’ll make it safely.

If you get the chance in the next few days, look at how Kane Williamson and Tom Latham run together for New Zealand, if indeed they get to the wicket at the same time in their Test against Pakistan. It’s underrated how well they work as a pair in that regard.

Not having that complete trust in Warner isn’t Labuschagne’s fault unless you’re a very hard marker, but it does lead to what happens next: he has a look, realises the trouble, stops, and only now calls ‘No’.

The problem is it’s happened too late: the pacy Warner is now three-quarters of the way to the striker’s end.

Image credit: Fox Cricket

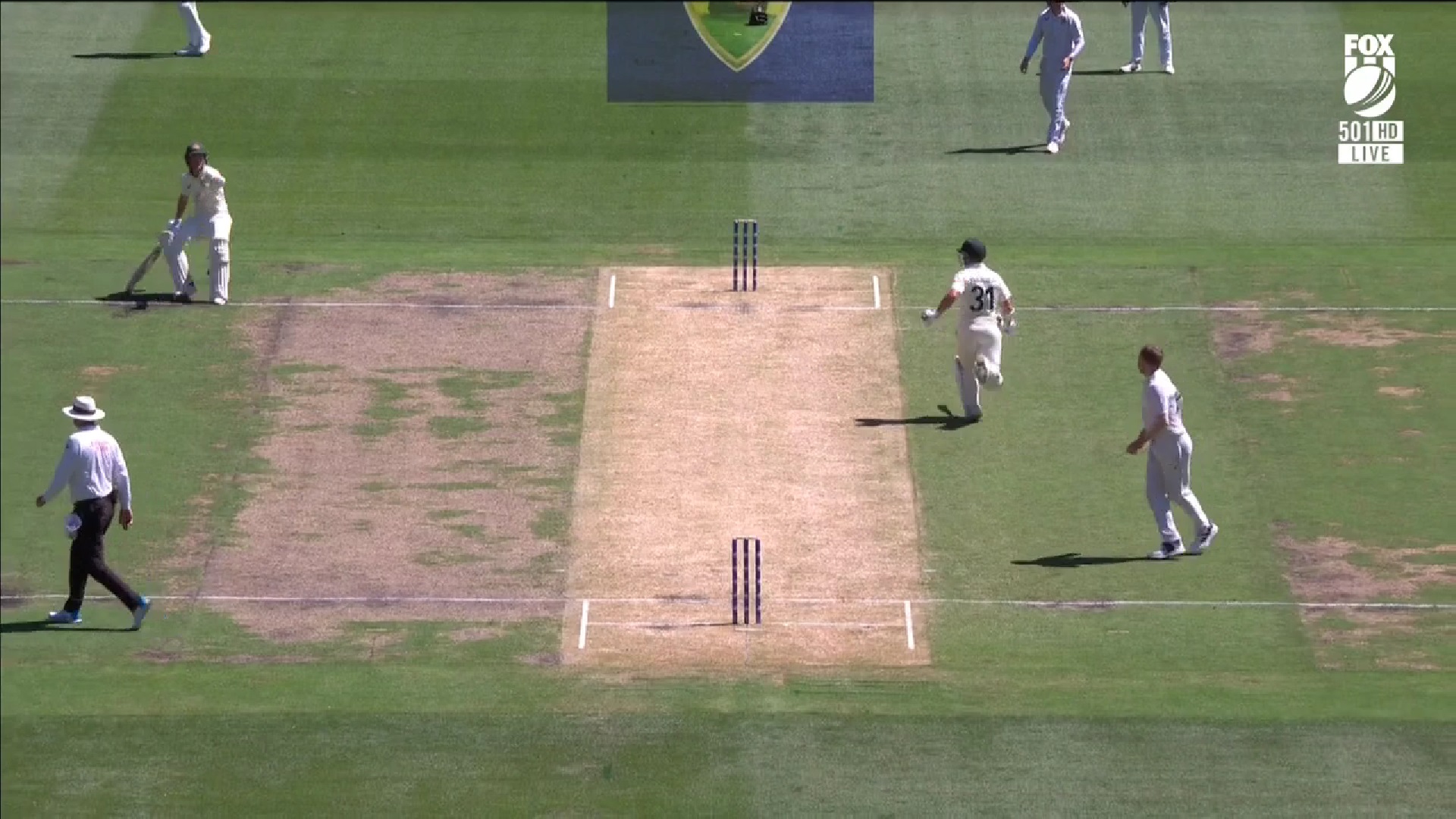

Nortje senses a run out is on, and begins to move into the stumps. Labuschagne, meanwhile, has stopped dead. Warner has seen him start to run, thought it safe to continue on, but hasn’t considered that his partner might have trusted him at the start, but backed out once he took a look at Maharaj.

Up next is where Labuschagne makes his fatal mistake. A run out from here is a definite chance, but it still needs a decent throw to Nortje. But Marnus gives South Africa a crucial extra second: once he decides it’s him that needs to run rather than Warner, he turns his head and watches the ball again, rather than sprinting with all his might for the other end.

Image credit: Fox Cricket

At this point, ball-watching is useless: Marnus already knows Maharaj has the ball, that’s why he stopped in the first place. All this latest head-turn achieves is slow him down – you can see him jink again a half-second later, when it first dawns to him that he’s in serious, serious trouble.

As it eventuated, Labuschagne was only fractionally short – he was considerably closer than Dean Elgar had been when the Queenslander himself had inflicted a run out on Day 1.

Image credit: Fox Cricket

That one extra moment of hesitation was probably the difference between him making his ground and not – and remember, thanks to it, Nortje was able to properly line up the stumps with his underarm and hit them.

Pressure can make the ball very difficult to handle, even for the simplest of run outs – remember Nathan Lyon at Headingley?

Warner was by no means blameless, but Marnus Labuschagne’s run out was certainly not his fault alone.

Labuschagne’s errors weren’t massive ones, but had he avoided them, he’d probably still be batting now.

Help shape the future of The Roar – take our quick survey with a chance to WIN!

>Cricket News

%20(3).jpeg)

0 Comments