How do you definitively rank Test batsmen from different eras? Armchair selectors have been posing this question since the 1800s.

The short answer is- you can’t.

Raw statistics are a blunt instrument with which to make comparisons. For example, Matthew Hayden’s average of 50.73 doesn’t mean that he was 30 per cent superior to Victor Trumper, whose own figure was 39.04.

When comparing players from different periods, the opinions of expert eyewitnesses are more reliable.

While the likes of Neil Harvey and Don Bradman stand accused of assessing their peers through rose-coloured glasses, are there any better judges, in the absence of action footage and identical conditions?

If there’s one thing on which we should agree, it’s that a champion in one era would have been a champion in any other. Lending weight to this theory is that the best players prospered in careers spanning decades.

If a pre-pubescent Clem Hill was spirited to 2014, he’d be a Test star by now.

If a teenaged Mark Waugh was transported to 1900, he’d prosper similarly.

While Trumper never contended with a pace battery, nor Steve Smith a limit on glove changes, natural ability would have ensured that each triumphed in the face of such unfamiliar challenges.

Averages are far from average

Conventional wisdom is that averages were lowest prior to WWI, peaked between the wars, and then rose again in the early-2000s.

Contemporary batsmen do score 20 per cent more runs than those of the nineteenth century, and record centuries and even half-centuries three times more frequently. They also hit boundaries far more regularly, and score more quickly.

However, the reality is far more nuanced. Scoring Test runs was neither always difficult in WG Grace’s era, nor always easy in that of Bradman.

Charlie Bannerman debuted with 165 in the inaugural Test in 1876/77, and Tip Foster with 287 in 1903/04. Conversely, Australia and South Africa lost 23 wickets in one day in Cape Town in 2011, while India was bowled out for 36 in Adelaide in 2020/21.

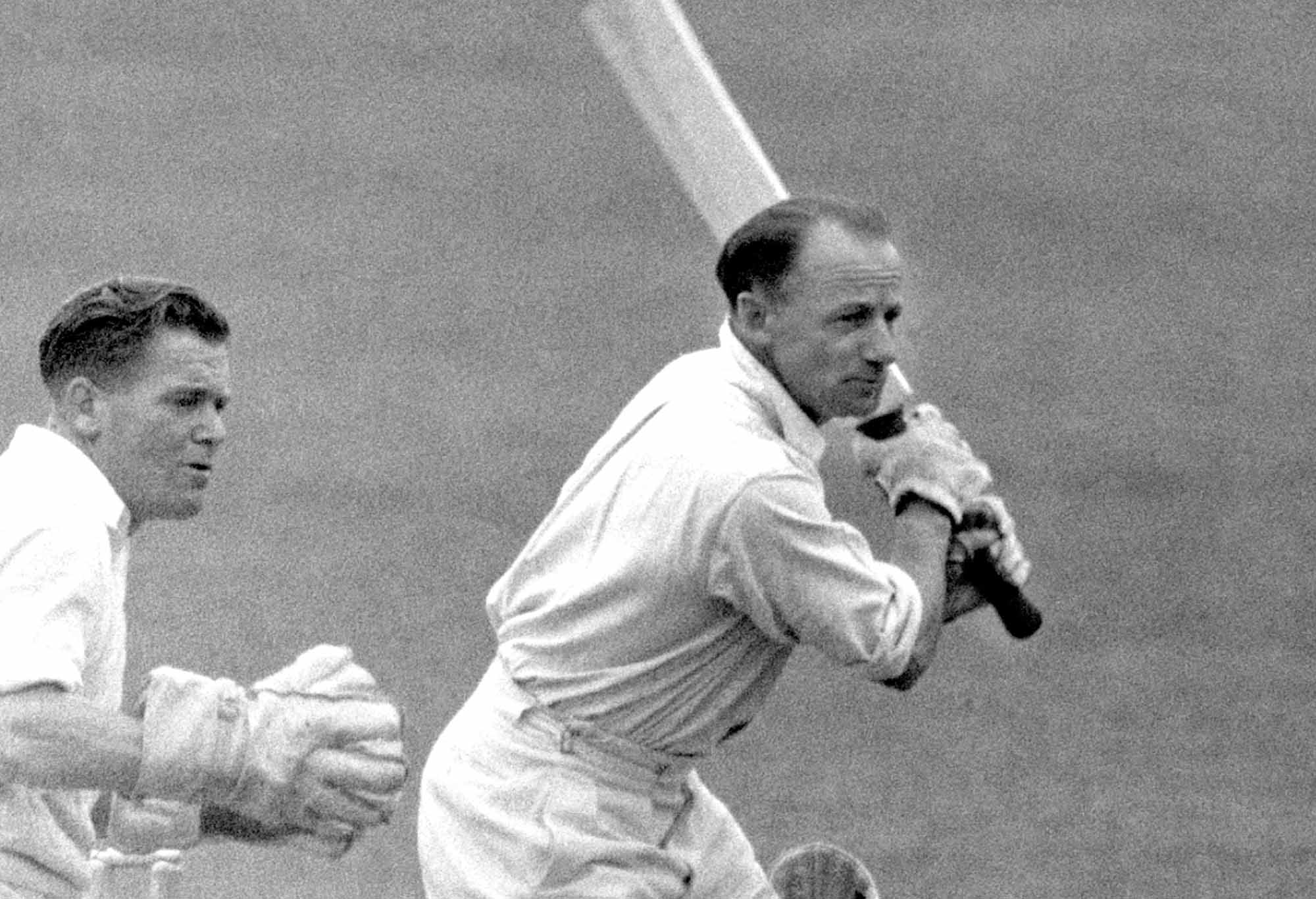

Sir Donald Bradman. (PA Images via Getty Images)

Overall averages have remained surprisingly stable. The figure for each nation’s home Tests is between 29.49 (for South Africa) and 33.49 (for Pakistan), apart from Ireland whose average for its single match is 27.61.

Nevertheless, that 14 per cent range is equivalent to the very same player averaging anywhere between 44.03 and 50.00, depending on the country in which he batted.

A global analysis underscores the folly of directly comparing averages. The highest-averaging decade of all was the 1940s (not the between-wars 1920s or 1930s), with an overall figure of 35.78.

While runs per wicket during the 2010s were 32.66 worldwide, contributing figures ranged from 43.63 when playing in Pakistan, down to just 28.56 in the West Indies.

In the 1950s, despite the average being 39.46 when in the West Indies, it was between 24.07 and 27.15 in each of Australia, England, New Zealand, Pakistan and South Africa.

The run-scoring of Bradman and his teammates is often downplayed on the basis that they batted on the flattest pitches in history.

Yet the average runs per wicket in Australia during the 1930s was just 28.65. The corresponding 2000s figure of 36.29 is 27 per cent higher, while the 2010s one of 35.33 is 23 per cent greater.

The 1930s average for matches in Australia is even lower than that of 29.45 for the 1890s, a decade generally perceived as having offered far tougher batting conditions.

A 5-10 run difference in average, from decade to decade, or nation to nation, might not appear significant.

Steve Smith. (Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

However, when it has been that low despite countless variations in laws, pitches, strategies, techniques and equipment, then it is clear that numbers alone can’t be used to rank batsmen who never played with or against each other, or even in the same countries.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate the degree to which changes in the game have affected figures, is to analyse modes of dismissal from 1877 to 2013.

The proportion of batsmen who were bowled was 36 per cent prior to WWI, yet only 16 per cent after 1993.

For the same two periods, the incidence of dismissal leg-before-wicket almost tripled from six per cent to 17 per cent, and of being caught by the wicketkeeper more than doubled from eight per cent to 18 per cent.

It’s simplistic in the extreme to suggest that these differences are a result of modern batsmen having become far better at protecting their stumps, while simultaneously far more likely to be struck on the pads or edge a delivery.

To illustrate the difficulties in comparing batsmen, two summaries follow. The first is of factors that made batting relatively easier in Test cricket’s earliest eras.

The second is of ones that have advantaged more recent batsmen.

The early days weren’t always a lottery

While batting prior to 1900 was often challenging, the very best batsmen were sufficiently skilled to make the most of favourable conditions when they did occur.

In addition to 85 team scores of less than 100, there were also 19 in excess of 400.

There were 14 instances of a batsman playing an innings of 150 or more, with WG Grace, Billy Murdoch and KS Ranjitsinhji each doing so twice.

Ironically, batsmen were assisted by the fact that poor pitches lessened the need for bowlers to develop new wicket-taking deliveries.

With an above-the-shoulder action only legalised in 1864, few bowlers could have mastered its possibilities before the inaugural Test took place 13 years later.

It would take until 1901 for George Hirst to exploit swing, and 1903 for Bernard Bosanquet to introduce the wrong-un.

Between 1901 and 1914, the legendary SF Barnes’ arsenal was the exception rather than the rule.

Clarrie Grimmett didn’t invent the flipper until the 1920s, nor did Jack Iverson deliver the doosra until the 1940s, while reverse swing was almost unheard of until the 1980s.

Clarrie Grimmett. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Until 1902, a pitch’s width was six feet rather than the current eight, limiting the variation in lines that a bowler could achieve.

Before 1927, the circumference of a ball was 6mm greater, making it slightly harder for a bowler to impart pace and movement.

Until 1931, a set of stumps was one inch lower and one inch narrower, reducing the size of the bowler’s target by 15 per cent. Before 1962, the back-foot no-ball Law gave a batsman additional time to take advantage of an umpire’s call.

Until 1937, a batsman could not be leg-before-wicket to a ball that pitched outside off stump, even if struck in-line.

Until 1972, a batsman could still pad up to a delivery that would hit the stumps, as long as he was struck outside the line.

That loophole was exploited perfectly by Peter May at Edgbaston in 1957, during a match-saving 411-run partnership with Colin Cowdrey against the West Indies.

Prior to WWII, no batsman ever faced a trio of genuinely-fast bowlers, for many and varied reasons.

Until 1897, there was no provision for a fielding side to ever take a second new ball. After rain, uncovered pitches could be impossible for bowlers with long run-ups to operate on.

Games played to a finish could last eight or nine days on pitches made to last, necessitating a reliance on slow bowlers.

Overs were delivered at a rate of 20 or more per hour, peaking at 24.1 during the Ashes series of 1891/92.

With helmets not utilised until 1978, sustained short-pitched bowling assaults were considered unsportsmanlike. There were exceptions, beginning with Jack Gregory and Ted McDonald in 1921.

However, no pace duos ever approached the intimidation levels of the great West Indian quartets of the late-1970s onwards.

While the game has always featured outstanding fieldsmen, the occasional poor one was generally accepted prior to the limited-over format’s arrival in 1971.

And fielding positions closer to the pitch were often assigned to bowlers, to conserve their energy. While that might have helped maintain high over-rates, it didn’t enhance the standard of slips catching.

Finally, Australia’s pre-WWI batsmen occasionally benefitted from England’s bowling not being at full strength when on tour.

Sometimes a professional would decline the terms offered, or an amateur prefer to remain home to indulge his non-cricketing interests.

Yorkshire refused to release Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes for the 1901/02 series lest they be overworked, while Barnes played in just 27 of a possible 59 Tests between 1901 and 1914.

Have batsmen ever had it so good?

While many factors that assisted batsmen have progressively disappeared, they have been replaced by even more favourable ones.

They help explain why both the 2000s and the 2010s rank among the highest-averaging decades of all time.

It recently proved necessary to restrict bats’ thicknesses, once they began to resemble railway sleepers rather than toothpicks.

Timber compression and moisture removal enhanced their sweet spots and power while maintaining their weight and balance.

While the introduction of floodlighting, roped boundaries, larger sightscreens and improved drainage may have been intended to improve safety and commercial returns, they also made run-scoring easier.

Mis-hits are now far more likely to result in sixes and fours. The frequency of all-run threes has plummeted.

Early-evening gloom is not the handicap that it once was – and overly-green pitches dry out more quickly.

(Paul Kane – CA/Cricket Australia via Getty Images/Getty Images)

The usage of helmets from 1978, and other protective equipment such as arm- and chest guards, has aided batsmen.

Where those with poor techniques were once found wanting, a suitably-armoured batsman can now indulge more safely in the forward press and front-foot pull-shot, or even take his eye off the ball while ducking.

Protection of pitches has been progressively extended and improved, especially since the 1980s. The artificial drying of a pitch was first allowed in 1932.

Covering was extended to the full length of a pitch in 1960, having previously protected only the creases and bowlers’ approaches.

While the occasional rain-affected pitch was once an accepted part of the game, nowadays one would be considered unfit even for a Fifth Grade match.

Programming has favoured batsmen. Mid-match rest days are long gone, while five-match series are compressed into seven or eight weeks, with games played back-to-back.

As a result, first-choice pacemen are rotated or play with minor niggles. Previously a leading paceman would sit out tour games, then return refreshed for the very next Test match.

Not only could a rest day give a bowler a longer break between innings, but it allowed a pitch an extra day in which to deteriorate and encouraged a captain to enforce the follow-on.

Batsmen haven’t had to contend with genuinely intimidatory or negative field placings since the 1930s.

A major factor in Bodyline’s success was the packing of the leg-side with fieldsmen, while previously slower or in-swing bowlers such as Armstrong and Fred Root did likewise to slow run-scoring.

The current limit of two fieldsmen behind square-leg assists batsmen to both defend themselves, and score runs.

Usman Khawaja. (Photo by Cameron Spencer/Getty Images)

Other technological developments have also improved the batsman’s lot.

From the 1920s onwards, marl and heavier motorised rollers helped flatten pitches and extend their life, while mechanised mowers improved pitches and created faster outfields.

Drop-in pitches have tended to deteriorate more slowly than permanent ones, as well as reduce variations between venues.

The abandonment of the eight-ball over in 1979 has arguably disadvantaged bowlers, especially spinners with longer-term wicket-taking strategies.

Until then, a fielding side in Australia, New Zealand or Pakistan could keep a struggling batsman on strike for two additional deliveries.

Modern batsmen now have crucial milliseconds longer in which to sight the ball.

Following the front-foot no-ball Law’s introduction in 1962, back-foot draggers such as Fred Trueman could no longer release the ball from well in front of the popping crease.

Finally, bowlers are no longer benefitting from suspect, but permitted actions.

During the 1950s and 1960s, batsmen had to contend with unfair deliveries from pacemen Charlie Griffith, Ian Meckiff, Cuan McCarthy and Geoff Griffin, and spinners Tony Lock and Jimmy Burke.

>Cricket News

%20(3).jpeg)

0 Comments