Steve Smith’s 2019 Ashes performance was the greatest individual batting performance in any test series in history.

Brian Lara’s 1999 Frank Worrell Trophy and Matthew Hayden’s 2001 Border-Gavaskar Trophy efforts are vying for the second spot.

Perhaps, Lara’s 2001-02 series in Sri Lanka may come in fourth given that a tie for second place equates to no third place.

Bradman’s 1930 (Ashes) effort pales in significance unless one only looks blindly at the sheer volume of runs in pure isolation without considering the following key things.

If we look at how the rest of the team fared in just first innings scores, then in 1930, the rest of the team scored 136, 6/475, 222, 331 and 463.

In 2019, it was 140, 158, 179, 7/278 and 145.

If we cap the 6/475 as 9/550, and the 7/278 as 9/330, then the average first innings total for Australia without Bradman in 1930 was 340, but only 180 without Smith in 2019.

Smith passed 50 on all four occasions he batted in a first innings, which is 100 per cent of the time, while Bradman passed it only three from five, so 60 per cent.

On three of Smith’s four occasions, he was the only player in his team to reach 50, whereas this didn’t happen on any of the three occasions Bradman passed 50.

Steve Smith (Visionhaus)

Across Bradman’s five first innings in 1930, there were the following scores of 50 or more (excluding Bradman): 64, 155, 81, 83, 50, 77, 54, 83, 51, 50, 54, 110, 73, 53 and 54.

This amounts to an average of 3 other 50+ scores per each first innings (excluding Bradman), for an average collective total runs per first innings of 218 from those additional 50+ scores.

Across Smith’s four first innings in 2019, there were only these additional 50+ scores from his colleagues: 67, 58 and 54.

This is a paltry average of 0.75 colleagues reaching 50, for an average collective total runs of 60.

There were also a mere two batsmen to pass 50 in the first innings in which Smith didn’t bat, and this only pulls the average number of colleagues up to a full ONE with the average collective total only rising to 63.

In the three first innings in which he passed 50 in 1930, Bradman went in at 1/162, 1/1 and 1/159.

Smith had to go in at 2/17, 2/60, 2/28 and 2/14.

So, Bradman went in, on average at 1/107, Smith at 2/30.

Smith also went in at 2 for -53 (i.e. trailing by 53 runs overall) in Australia’s second innings of the first Test.

So dominant were the entire Australian batting line-up in 1930, that the team only batted twice on two occasions, one of those just mopping up a mere 72.

The other occasion was an irretrievable fourth innings lost cause, having been set a target in excess of anything that has ever been successfully chased down to this very day, nearly an entire century later.

Individual innings like Bradman’s 131 in such instances represent little more than the final thrusts of a dying fish. Matthew Wade’s 117 at the Oval in 2019 falls into the exact same category.

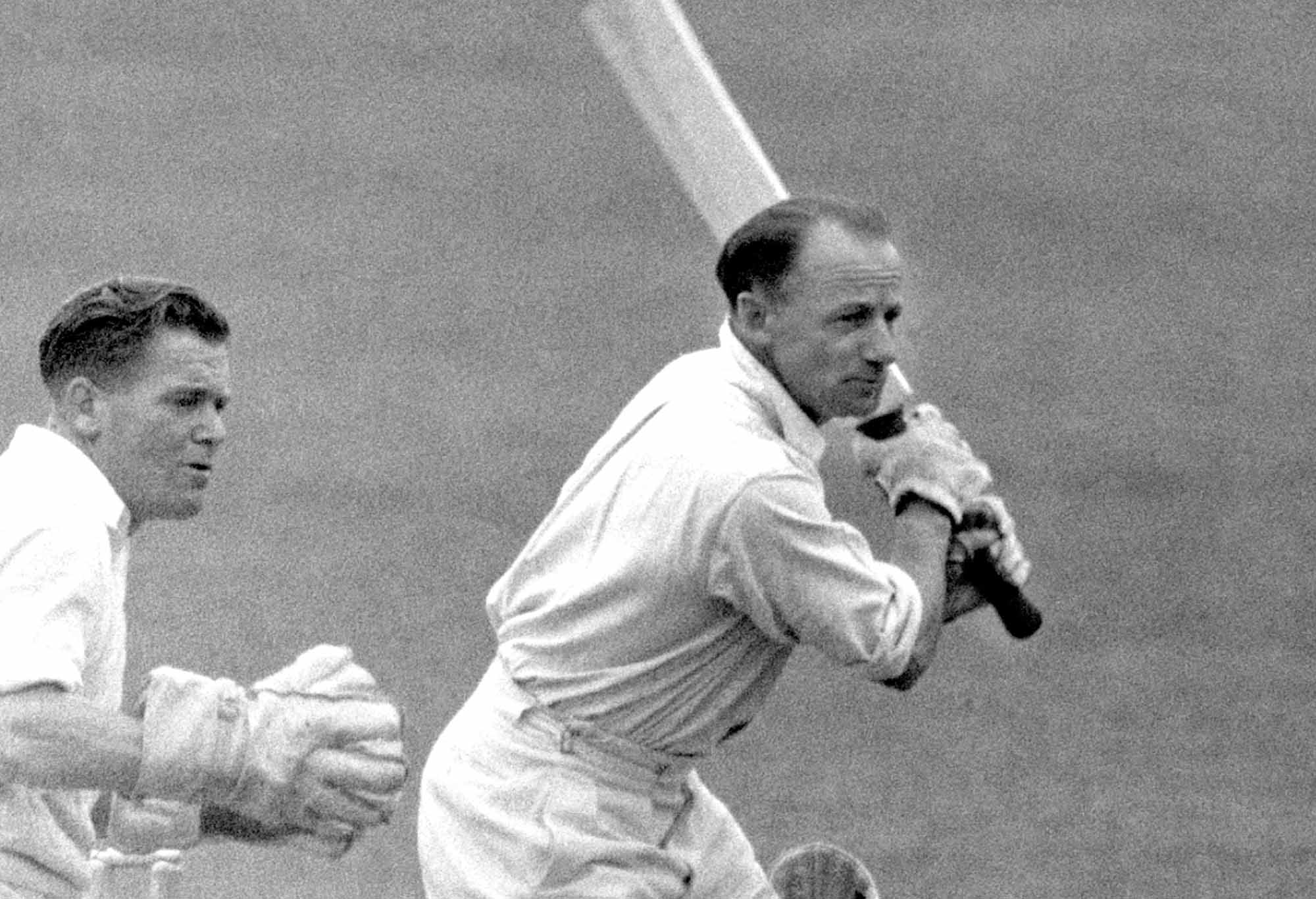

Sir Donald Bradman. (PA Images via Getty Images)

Both centuries by Bradman’s colleagues in 1930 were scored in Australia’s first innings of that particular game, in both cases replying to large opposition first-up totals of 425 and 405.

The only other century for Australia in 2019 was by Wade in the third innings of the first test – while there was still a lot of work to do, he went in with Smith having almost single-handedly retrieved Australia’s position from a crisis situation of 2 for -53 to now being potentially back in the match at 4 for +115.

Finally, the opposition attacks: Smith had to contend with Stuart Broad, Jofra Archer, Chris Woakes and Sam Curran, all master exponents of swing bowling in English conditions, while Bradman faced only an over-the-hill Tate and a flat, miss-firing Larwood on mostly featherbeds.

The timeless Oval test is a case in point: so flat and docile was the pitch, that the aforementioned Harold Larwood and Maurice Tate took a wicket only every 339 balls they bowled and finished with a collective 2 for 285.

One of them Bradman’s token wicket after scoring 232, and the other the number 11 when Australia were already 291 in front.

Those aforementioned 2019 bowlers took a wicket every 49.2 balls bowled at a cost of 26.5.

In their Australian opposition’s pivotal first innings that series, they took a wicket every 42.6 balls bowled, at a miserly cost of 21.9 – all this is in amongst Smith scoring 144, 142, 92, 219, 82, 80 and 23.

In 1930, all the Australian batsmen were able to score quite heavily, in 2019, Smith alone.

Needless to say, without Bradman in 1930, Australia could still conceivably have won 2-1, whereas, without Smith 89 years later, a 0-5 drubbing at our expense is a foregone conclusion – and it’s not even up for debate.

>Cricket News

%20(3).jpeg)

0 Comments