Over hundreds of episodes of Story Time, the history spin-off to beloved podcast The Final Word, Geoff Lemon and Adam Collins have followed their listeners’ clues to track down the wildest characters, matches, and situations the pitch has seen. Bedtime Tales for Cricket Tragics brings together the stories they enjoyed telling most, from the 1879 riot in Sydney sparked by an umpire’s call, the all-rounder who tried to rob the Catholic Church, the biggest defeat in history, and much more.

4.18 … Clue sent by: Jamo

Playing two Tests with best figures of 4 for 18 doesn’t yell ‘legend’. But our clue from Jamo mentioned this player being a Swans tragic, same as Jamo’s grandfather. The Swans Aussie rules team plays in Sydney now, but for over a century were South Melbourne, and once we made that connection, there was little doubt that this clue led to Laurie Nash.

And let us tell you, Laurie Nash was certainly a legend, in terms of two sports, one world war, and an entertainingly high level of self-belief. More than any Australian cricketer, Laurie spoke his mind.

Laurie was a good Melbourne lad, born in Fitzroy in 1910, when all the guys had much the same moustaches as they do now. He was strong, stocky, and a bull at a gate. Being short wasn’t going to stop him being a fast bowler.

He belted in and belted the ball down, often halfway down the wicket. He was playing first-grade cricket for Fitzroy by 17 and was being looked at for Victoria until the family suddenly moved to Tasmania.

Laurie liked a scrap, on the field or off it, and his dad was similar. Bob Nash had been a champion footballer who captained Collingwood and Footscray, played state matches for Victoria, got in trouble at the tribunal for belting opponents and arguing with umpires, and at 74 years old died at a Collingwood game.

That’s commitment.

After playing footy Bob became a copper, and was naturally of the temperament to join a police strike. Sacked, he upped sticks to Tassie with the family to run a pub. By 19, Laurie was playing first-class cricket for the state and senior footy in the northern Tasmanian league.

Laurie’s combativeness was apparent. He lipped off deluxe. He was fiery, stubborn, blunt, and put people offside. He cut the sleeves off his cricket shirts because they got in the way.

He wasn’t known for batting, but twice in his first three games Tasmania had to follow on against Victoria, and Laurie responded by coming in down the order and smashing the team’s highest score, 48 and 55 respectively. Against the Vics again in 1931, he got so pissed off that he started deliberately throwing, getting pinged by the umpire in the process.

He went on to take five wickets, having already smashed his only first-class hundred as a pinch-hitting opener. Later that year he got his first win over the Big V, dominating with 84 in a run chase. Off the field, he was just as much a stubborn bastard.

His family was Catholic, but he married Irene, a Protestant, in an era when that was not the done thing. They had the wedding in Irene’s church, and for the rest of her life, the Catholic Church badgered Laurie to have another ceremony at one of theirs, saying that his marriage didn’t count.

If we can paraphrase, he replied with something like, ‘Bugger off. I’m Laurie Nash. I love my wife, and I don’t give a shit.’

In January 1932, with the South Africans touring Australia, Laurie played them twice for Tassie. After a modest draw in his home town of Launceston, he headed to Hobart and unleashed. He had Bruce Mitchell caught behind, then clean bowled Jim Christy.

On a hat-trick, against the touring side in the middle of a Test series, what do you do? Bowl off stump? Knock him over, draw a nick? Not Laurie. He bowled a bouncer and broke Eric Dalton’s jaw. F–k hat-tricks.

Laurie got 7 for 50 that day, and roughing up the tourists did get him in for the fifth Test. He was 21 years old. He started with a spell of three wickets for four runs, sparking the slide that saw South Africa bowled out for 36 and 45: the fifth and 16th lowest Test totals in the one match.

In the first innings, Laurie also took out the captain to finish with the aforementioned 4 for 18, and in the second innings he clean bowled Christy first ball, just as he had in Hobart.

So, 5 for 22 in your first match should get you a run at the top level, right? The problem was that Australia’s next assignment was the following summer, the 1932/33 Ashes. You may have heard about that series. Laurie’s wildness of

character went against him with selectors who were worried about what aristocrats at Marylebone Cricket Club would think.

And once the series began, it soon became what would be known as Bodyline.

With tempers at breaking point, riots brewing, and relations between the countries at an all-time low, nobody was brave enough to pick a tinderbox player like Laurie Nash.

On the other hand, a fast, angry, intimidating fast bowler just might have been an asset for Australia in a series when Harold Larwood was trying to hit everyone in the head. Laurie certainly thought so. His quotes all get paraphrased in different directions, but he said something like this: ‘If they’d picked me, Bodyline would have been done in two overs.’

Harold Larwood bounces Bill Woodfull. (Central Press/Getty Images)

Confident in his ability and aggrieved that it wasn’t being used, Laurie was jack of cricket, so he moved back to Victoria with his brother to take up an offer to play football for South Melbourne. He was already a good player, but he turned into an absolute gun.

Massively undersized for the job at five-foot-nine, he nonetheless played centre half-back, not just taking on much bigger opponents but marauding down the ground to set up play like a modern backman. Later he would start

swinging through centre half-forward and even into the ruck. Whatever job needed doing, Laurie would fix it.

In his first season, the Swans won the flag, and Laurie would have won the Norm Smith if it existed then, best on ground. In his second, with licence to drift, he kicked 53 goals on the way to another grand final. In his third, he got picked for Victoria to play state footy against South Australia, and on a whim was thrown in at full-forward.

He kicked 18 goals that day. There was more vintage Laurie after the game: ‘I would have kicked a lot more if anyone had passed to me.’

He was playing cricket for South too, dominating Melbourne firstgrade every summer, but every summer the Vics refused to pick him. Finally, during a gap in the schedule after the fourth Ashes Test in February 1937, he was asked to play for Victoria against the tourists. It was his first match for his original home state.

This Ashes series might be the best ever: England winning the first two Tests, Australia the next two, in a turnaround whose story we’ll tell in a later chapter. The fifth Test was the decider, and all options were on the table. In that moment, five years since his debut, Laurie walked out against the English in this state match and beat them up.

He didn’t take a bag, but his four wickets for the match were all top-three batters, and more importantly, he went hard at them. He bowled fast, short, and unsociably. England didn’t like it. When Bill Woodfull was captain, he didn’t like it

either. But now, Don Bradman was in charge, and he had some flint.

He told selectors that this was the guy he wanted, and in this critical moment, they finally said yes.

The English were spooked. Gubby Allen was their captain, a bloke with a number of dubious moments in his relationship with Australia, even though he was the bowler who had refused to use Bodyline tactics on his previous visit. This time, though, he tried to get Laurie barred from playing in the Test.

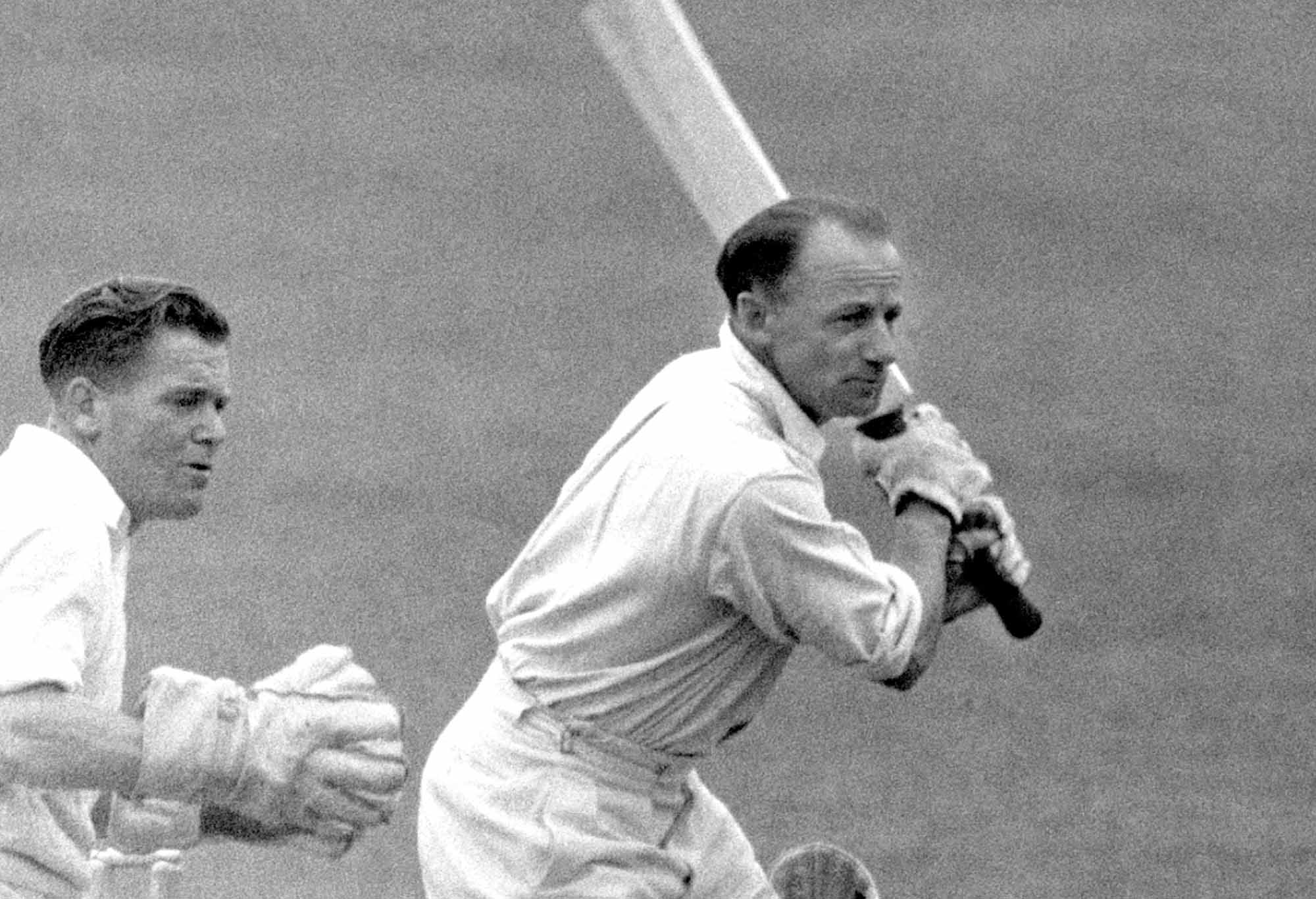

Laurie Nash in delivery stride.

Gubby first lobbied Don, then the Australian board, and his own lot in London, complaining that Laurie was too

aggressive in bowling bouncers. It was class politics laid bare. Australia’s board was faltering under the pressure, until the selectors said that if he were withdrawn, they would create a scandal by resigning en masse, forcing the story to become public.

So finally, at 27 years old, Laurie got picked for his second Test. In the end, aggressive bowling wasn’t the decisive factor, given Australia batted first and piled on 604. Surprise, surprise, big Bradman hundred. But it was a timeless

Test, so England too could have gone big in reply. Instead, Laurie took 4 for 70 to help pack them up for 239, meaning Bradman could enforce the follow-on.

The third innings was mostly for the spinners, with Laurie adding one more victim. That made 10 wickets at 12 in his career, helping that Australian team do what no other has ever done: come back from two Tests down to win a series.

In another classic paraphrase, he said, ‘With the score at 2–all they knew where to come.’ And that, stunningly, was the final first-class match that Laurie Nash ever played.

Soon afterwards he was invited to play his first Sheffield Shield match for Victoria.

But we’ve already established that he loved his wife, so when Irene fell sick he pulled out of the trip. Soon afterwards, he rolled up in first grade and took all 10 wickets in an innings against Prahran. They’re still the best first-grade figures in Victoria. Even then, his state never made the offer again.

Nor did his country, though Bradman wanted him to tour England in 1938. Without the anxiety of 2–2, the stuffed shirts overruled Don. Their conservatism won the day, instead of backing their own. The superstar Keith Miller, a teammate at South Melbourne, called it ‘the greatest waste of talent in Australian cricket history’, and he has a point.

Laurie kicked hundreds more goals after switching from the Victorian Football League to the rival Victorian Football Association, and when asked who was the best footballer he’d ever seen, he said, ‘I see him every morning when I look in the mirror.’

Sir Donald Bradman. (PA Images via Getty Images)

After Japan declared war in 1941, he joined up and fought in New Guinea, and in true Laurie style, refused all preferential treatment and promotions. He even knocked back his campaign medals, saying he had only wanted to do his bit.

Footy leagues continued through the war, but by the time Laurie got home he was 35, too heavy, with crocked knees. Still, in 1945 he signed up for one last season with South Melbourne, temporarily at the Junction Oval in St Kilda, with their home ground overtaken by the army.

Despite spending each Sunday in hospital getting fluid drained from his joints, Laurie led the goalkicking and led the Swans to the top of the ladder, then into a grand final. He didn’t finish the fairytale by going out with a premiership, but he did complete his career in Laurie Nash style, with the last punch of a grand final written up as ‘The Bloodbath’.

After Carlton captain Bob Chitty had decked two Swans players, Laurie wanted payback. ‘I was after him, and I got him.

And even if I say so myself, it was a perfect left hook. It laid Chitty out cold.’

That may not make Laurie the role model of choice for a young athlete, but he was the living embodiment of some old advice: be yourself; everybody else is taken.

This is an edited extract from Bedtime Tales for Cricket Tragics by Geoff Lemon and Adam Collins, out November 25 with Affirm Press.

>Cricket News

%20(3).jpeg)

0 Comments